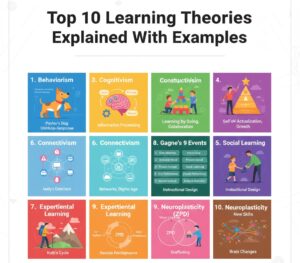

From the earliest days of formal education to the AI-powered adaptive platforms of today, the quest to understand how humans learn has been a driving force in psychology and pedagogy. Learning theories provide the frameworks that explain the processes behind knowledge acquisition, shaping everything from classroom layouts to corporate training modules and language-learning apps.

For educators, trainers, instructional designers, or simply curious minds, understanding these theories is not an academic exercise—it’s a practical toolkit for designing more effective, engaging, and impactful learning experiences. Here, we explore ten foundational and influential learning theories, breaking down their core principles with concrete, modern examples.

For educators, trainers, instructional designers, or simply curious minds, understanding these theories is not an academic exercise—it’s a practical toolkit for designing more effective, engaging, and impactful learning experiences. Here, we explore ten foundational and influential learning theories, breaking down their core principles with concrete, modern examples.

1. Behaviorism: Learning as Observable Change

Core Idea: Behaviorism, championed by B.F. Skinner and Ivan Pavlov, focuses solely on observable behaviors, ignoring internal mental states. It posits that learning is a process of conditioning, where behaviors are shaped by their consequences through reinforcement (increasing a behavior) or punishment (decreasing a behavior).

Key Concepts: Classical Conditioning (Pavlov’s dogs), Operant Conditioning (Skinner’s box), Positive/Negative Reinforcement, Punishment.

Modern Example: Fitness Apps and Gamification. When you complete a daily workout on an app like Strava or Duolingo, you receive immediate positive reinforcement: celebratory sounds, achievement badges, points, and a streak counter. This reward strengthens your behavior, making you more likely to log in and complete a task the next day. Similarly, a sales team bonus for hitting a quarterly target is a direct application of positive reinforcement in operant conditioning.

2. Cognitivism: The Mind as an Information Processor

Core Idea: Reacting to behaviorism’s limitations, cognitivism (pioneered by Jean Piaget and Ulric Neisser) shifts the focus to the internal mental processes involved in learning: thinking, memory, problem-solving, and information processing. The mind is viewed as a computer-like system that inputs, stores, organizes, and retrieves information.

Key Concepts: Schema (mental models), Information Processing Model (sensory memory, working memory, long-term memory), Metacognition (thinking about thinking).

Modern Example: An Interactive Cybersecurity Training Module. Instead of just rewarding correct answers, a strong cognitivist design would first help learners activate their existing “schema” about online security. It would then present new information (e.g., on phishing) in organized, bite-sized chunks to avoid overloading working memory. It would use analogies (comparing a firewall to a bank security guard) to link new knowledge to existing schemas, and include summarization tasks to encourage encoding into long-term memory.

3. Constructivism: Building Knowledge Through Experience

Core Idea: Associated with Lev Vygotsky and John Dewey, constructivism asserts that learners do not passively receive knowledge; they actively construct their own understanding and meaning of the world through experiences and reflection. Learning is a personal, social, and contextual process.

Key Concepts: Active Learning, Discovery Learning, Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD—the gap between what a learner can do alone and with guidance), Scaffolding.

Modern Example: Project-Based Learning (PBL) in a Classroom or Workplace. A teacher or manager doesn’t lecture on “sustainable business.” Instead, they pose a complex, real-world problem: “How can our school/office reduce its waste by 30%?” Learners form teams, research, experiment with composting or recycling audits, analyze data, and propose solutions. They construct deep knowledge through the active process of inquiry, collaboration, and creating a tangible product. The instructor acts as a facilitator, providing “scaffolding” (resources, check-ins) to support learners within their ZPD.

4. Social Learning Theory: Learning by Observing Others

Core Idea: Albert Bandura’s seminal theory bridges behaviorism and cognitivism. It emphasizes that people can learn new behaviors and information by observing, imitating, and modeling others, even without direct reinforcement. Attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation are key processes.

Key Concepts: Observational Learning, Modeling, Vicarious Reinforcement (learning from seeing others be rewarded).

Modern Example: “How-To” Video Tutorials on YouTube. A person learns to change a car tire, cook a soufflé, or use a complex software feature not by trial-and-error or reading a manual, but by watching a skilled peer demonstrate the process. The learner pays attention to the key steps (attention), remembers the sequence (retention), attempts it themselves (reproduction), and is motivated by the successful outcome they observed (vicarious reinforcement). This is also the principle behind mentorship programs and apprenticeships.

5. Humanism: Learning for Self-Actualization

Core Idea: Humanist theories, led by Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, place the whole person—their emotions, experiences, and drive for personal growth—at the center of learning. The goal is self-actualization: fulfilling one’s potential. Learning is student-centered and must be relevant to the learner’s goals.

Key Concepts: Learner-Centered Education, Self-Directed Learning, Unconditional Positive Regard, The Hierarchy of Needs (learning is hindered if basic physiological and safety needs aren’t met).

Modern Example: A Self-Paced, Choice-Driven Professional Development Plan. Instead of mandatory, generic training, a company using a humanist approach allows employees to design their own learning paths aligned with their career aspirations and personal interests. A manager provides supportive coaching (“unconditional positive regard”) and resources, while the employee chooses to take a course on leadership, creative writing, or data visualization based on their own goals for growth and self-actualization.

6. Connectivism: Learning in the Digital Network

Core Idea: Proposed by George Siemens and Stephen Downes for the digital age, connectivism argues that in an era of rapid information turnover, the ability to know where to find current knowledge is more critical than possessing knowledge itself. Learning is the process of creating connections and navigating networks—both neural, conceptual, and social/digital.

Key Concepts: Network Creation, “The pipe is more important than the content within the pipe,” Decisional Learning (knowing what to learn next).

Modern Example: A Data Scientist Using Online Networks. Their primary skill isn’t just memorizing algorithms (which constantly evolve). It’s knowing how to cultivate a “Personal Learning Network” (PLN): following leading experts on Twitter/X, engaging in specialized subreddits like r/MachineLearning, curating feeds from arXiv.org for pre-print papers, and contributing to GitHub communities. Learning happens by connecting to nodes (people, databases, journals) in a dynamic information ecosystem.

7. Experiential Learning Theory: The Learning Cycle

Core Idea: David Kolb’s model posits that learning is a cyclical process rooted in experience. Effective learning requires four stages: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization (forming theories), and Active Experimentation (testing theories). Learners often have a preferred style within this cycle.

Key Concepts: The Learning Cycle (Experience, Reflect, Think, Act), Learning Styles (Diverging, Assimilating, Converging, Accommodating).

Modern Example: A Startup “Fail Fast” Sprint. A team launches a minimal version of a new app (Concrete Experience). They analyze user data and feedback, asking, “What went wrong?” (Reflective Observation). They hypothesize that the main feature is confusing and develop a new theory about user onboarding (Abstract Conceptualization). They quickly redesign and release an updated version to test their hypothesis (Active Experimentation). The cycle then repeats.

8. Multiple Intelligences: Beyond a Single IQ

Core Idea: Howard Gardner’s theory challenged the notion of a single, general intelligence (IQ). He proposed at least eight distinct intelligences that individuals possess in varying blends: Linguistic, Logical-Mathematical, Spatial, Bodily-Kinesthetic, Musical, Interpersonal, Intrapersonal, and Naturalist.

Key Concepts: Diverse Modalities of Intelligence, Differentiated Instruction.

Modern Example: Teaching a Historical Event in a Classroom. A teacher might offer multiple pathways to understand the Renaissance: reading primary sources (Linguistic), analyzing trade route maps (Spatial), creating a timeline of scientific discoveries (Logical-Mathematical), performing a short play from the period (Bodily-Kinesthetic/Interpersonal), or composing music inspired by the era (Musical). This allows students to engage with the material through their strengths and develop other intelligences.

9. Adult Learning Theory (Andragogy)

Core Idea: Malcolm Knowles distinguished andragogy (the art of teaching adults) from pedagogy (teaching children). Adults are self-directed, bring a wealth of life experience to learning, are goal-oriented, seek relevance, and are motivated by internal factors rather than external ones.

Key Concepts: Self-Direction, Experience as a Resource, Readiness to Learn (linked to real-life tasks), Problem-Centered Orientation.

Modern Example: A Coding Bootcamp for Career Changers. The curriculum isn’t taught like a standard academic computer science course. It is intensely problem-centered (build a real web app by week 6). It leverages adults’ experiences (a former marketer might work on an app for that industry). Learning is self-paced within cohorts, and the immediate relevance to landing a new job provides powerful internal motivation.

10. Cognitive Load Theory: Optimizing Mental Effort

Core Idea: Developed by John Sweller, this theory focuses on the architecture of working memory, which has a very limited capacity. Effective instructional design must manage the type of “load” on a learner’s mind to avoid overload and facilitate the creation of long-term memory “schemas.”

Key Concepts: Intrinsic Load (complexity of the material), Extraneous Load (poorly designed instruction that wastes mental resources), Germane Load (mental effort devoted to processing information and building schemas).

Modern Example: A Well-Designed eLearning Module. To minimize extraneous cognitive load, a good module avoids “split attention” (e.g., narration that describes a diagram placed on a separate screen). Instead, it uses audio that explains elements directly on the diagram (co-located text and graphics). It breaks complex procedures into animated step-by-step sequences and removes decorative, irrelevant graphics or background music. This frees up working memory capacity to deal with the intrinsic load of the new content and engage in germane processing.

Synthesizing the Theories: A Practical Approach

The power lies not in choosing one “best” theory, but in strategically blending them. A modern learning experience might:

-

Use behaviorist principles for habit formation (gamification streaks).

-

Structure content with cognitivist principles to manage cognitive load.

-

Create constructivist and experiential group projects.

-

Leverage social learning through peer video reviews and communities of practice.

-

Be delivered on a connectivist platform that links to dynamic resources.

-

Respect andragogical principles by making it relevant and self-directed for adult professionals.

Understanding these theories provides a map to the complex terrain of the human mind. By applying their insights, we can move beyond one-size-fits-all instruction and design learning journeys that are more efficient, engaging, and ultimately, more human.