For centuries, learning was a black box—a mysterious process of transferring knowledge into the mind. Today, neuroscience has unlocked that box, revealing a breathtakingly complex, dynamic, and physical process. Learning isn’t just a metaphor; it’s a tangible biological event that literally reshapes the brain.

Understanding this science—the dance of neurons, the strengthening of pathways, and the consolidation of memory—transforms how we approach education, skill acquisition, and personal development. This is the story of how a three-pound organ of fat and protein builds our reality, one connection at a time.

The Fundamental Unit: The Neuron and the Synapse

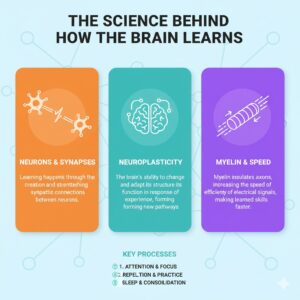

The brain’s basic building block is the neuron, a specialized cell designed to transmit information. Each neuron has a cell body, branch-like dendrites (which receive signals), and a long, trunk-like axon (which sends signals). Neurons don’t touch; the tiny gap between the axon of one neuron and the dendrite of another is called a synapse.

Learning, at its most fundamental physical level, occurs at this synaptic gap. The mantra of modern neuroscience is “neurons that fire together, wire together.” Coined by psychologist Donald Hebb, this principle (Hebbian plasticity) states that when two neurons are activated simultaneously, the connection between them strengthens. Repeated co-activation makes communication across that synapse faster, more efficient, and more likely in the future.

Learning, at its most fundamental physical level, occurs at this synaptic gap. The mantra of modern neuroscience is “neurons that fire together, wire together.” Coined by psychologist Donald Hebb, this principle (Hebbian plasticity) states that when two neurons are activated simultaneously, the connection between them strengthens. Repeated co-activation makes communication across that synapse faster, more efficient, and more likely in the future.

Example: When a child first sees a dog and hears the word “dog” spoken, visual neurons and auditory neurons fire. If this pairing is repeated, the synapses connecting these neural networks strengthen. Eventually, just seeing the dog will activate the sound of the word in the brain, and hearing the word will conjure a mental image. A new concept has been physically wired into the brain’s circuitry.

The Chemical Ballet: Neurotransmitters and Reinforcement

How does a synapse strengthen? It’s a chemical and structural ballet. When an electrical signal reaches the end of an axon, it triggers the release of neurotransmitters—chemical messengers—into the synaptic gap. These bind to receptors on the receiving dendrite, passing the signal along.

Key neurotransmitters in learning include:

-

Glutamate: The primary workhorse for excitatory signals. It is crucial for long-term potentiation (LTP), the persistent strengthening of synapses based on recent patterns of activity, considered the cellular basis for learning and memory.

-

Dopamine: Often mislabeled as the “pleasure chemical,” its core role in learning is reward prediction and motivation. Dopamine is released not just when we get a reward, but when we anticipate one. This release flags an experience as “important,” directing attention and telling the brain, “Remember what just happened so you can repeat it.” It strengthens the synaptic connections of the actions leading to the reward.

-

Acetylcholine: Essential for attention, focus, and neuroplasticity. It primes the brain to be more receptive to new information and signals which experiences should be encoded into long-term memory.

Example: A student solves a difficult math problem and feels a surge of satisfaction. That positive feeling is accompanied by dopamine release, which consolidates the neural pathway used to solve that problem. The brain learns not just the solution, but also to associate the effort of problem-solving with a rewarding outcome, increasing future motivation.

The Anatomy of Learning: Key Brain Regions in Concert

Learning is not localized to one spot; it’s a symphony performed by a network of brain regions:

-

The Hippocampus: The Gateway to Memory

This seahorse-shaped structure is the brain’s memory formation center. It acts as a sort of “save” button, binding together disparate sensory details (sights, sounds, context) from other cortical areas into a single, coherent memory trace during an event. These traces are then gradually transferred to the cerebral cortex (particularly the prefrontal cortex) for long-term storage over days, months, or years—a process called memory consolidation. -

The Prefrontal Cortex: The Executive Conductor

Located behind the forehead, this region is responsible for working memory (mentally holding and manipulating information), focus, decision-making, and complex thought. It’s the “CEO” of the brain, directing attention to relevant stimuli and inhibiting distractions, which is the critical first step for any learning. -

The Amygdala: The Emotional Spotlight

This almond-shaped cluster tags memories with emotional significance. High-emotion events (both positive and negative) trigger the amygdala to signal the hippocampus: “This is important! Consolidate this memory strongly.” This is why we vividly remember where we were on 9/11 or our wedding day—emotion enhances synaptic plasticity. -

The Cerebellum: The Skill Programmer

Once thought to be only for balance and coordination, the cerebellum is now known as critical for procedural learning—the learning of motor skills and habits. It fine-tunes the timing and accuracy of movements, from playing the piano to riding a bike, through extensive practice that builds highly efficient, unconscious neural pathways. -

The Basal Ganglia: The Habit Center

This deep-brain network is central to reward-based learning and habit formation. It takes over routine behaviors that have been practiced extensively (like brushing your teeth or driving a familiar route), freeing up the prefrontal cortex for novel tasks.

Example: Learning to Drive a Car

-

Initially, the prefrontal cortex is overwhelmed—focusing on mirrors, pedals, steering, and rules all at once (high cognitive load).

-

The hippocampus works to form a new memory of the route and procedures.

-

With practice, control of steering and gear-shifting shifts to the cerebellum (making movements smooth).

-

Eventually, the routine of commuting on a known route is handed off to the basal ganglia (becoming a habit you perform on “autopilot”), allowing your prefrontal cortex to plan your day or listen to a podcast.

The Mechanisms of Change: Neuroplasticity in Action

The brain’s ability to change its structure and function in response to experience is called neuroplasticity. It is the physical manifestation of learning.

-

Synaptic Plasticity: As described, this is the strengthening (long-term potentiation, or LTP) or weakening (long-term depression, LTD) of existing synapses. Practice strengthens pathways; disuse weakens them (“use it or lose it”).

-

Structural Plasticity: More profound learning can lead to physical changes. This includes:

-

Dendritic Branching: Neurons can grow new dendritic spines (the tiny protrusions that receive signals), creating more potential connection points.

-

Neurogenesis: The birth of new neurons, primarily in the hippocampus. While once thought impossible in adults, we now know that factors like aerobic exercise, learning, and a stimulating environment can promote neurogenesis, providing fresh “hardware” for new memories.

-

Example: A Taxi Driver’s Hippocampus. Famous London taxi drivers, who must memorize the city’s immense “Knowledge,” have been shown to have significantly larger posterior hippocampi compared to non-taxi drivers. The volume correlates with time on the job. Their brains structurally changed to accommodate their extraordinary spatial memory.

The Critical Role of Sleep and Spacing

The brain doesn’t stop learning when we stop studying. Two of the most powerful learning processes happen offline.

-

Sleep: The Master Consolidator

During deep slow-wave sleep, the hippocampus replays the day’s neural activity patterns, transferring memories to the cortex for long-term storage. During REM sleep, the brain strengthens procedural memories and makes novel connections between disparate ideas, fostering creativity and insight. Depriving yourself of sleep after learning is like hitting “save” on a document but never transferring it to your hard drive—the data is fragile and likely to be lost. -

The Spacing Effect (Distributed Practice):

Cramming creates strong short-term memories that fade quickly. Spacing out study or practice sessions over time is far more effective for long-term retention. The science behind this is that each time you recall information after a forgetting curve has begun, the memory trace must be reconsolidated. This reconsolidation process strengthens the memory and makes it more resistant to forgetting.

Example: Learning a Language. Studying vocabulary for 30 minutes a day for 10 days is vastly superior to studying for 5 hours straight. The spaced practice forces repeated retrieval and reconsolidation. A good night’s sleep after each session then solidifies those words into long-term memory, building fluency.

Practical Implications: Learning with the Brain in Mind

Understanding this science allows us to design better learning strategies:

-

Embrace Desirable Difficulty: The brain learns best when it has to work. Self-testing, interleaving different topics (mixing math problems instead of blocking by type), and practicing retrieval are more effortful but create stronger, more durable memories than passive re-reading.

-

Harness Attention: The prefrontal cortex needs focus. Minimize multitasking and digital distractions to allow acetylcholine to do its job of priming neural networks for encoding.

-

Connect to Emotion and Meaning: Link new information to existing knowledge (building on existing schemas) or personal stories. Emotional relevance, driven by the amygdala, triggers deeper processing.

-

Move and Sleep: Aerobic exercise increases blood flow, neurogenesis, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a “fertilizer” for neurons. Prioritizing sleep is non-negotiable for memory consolidation.

-

Practice Deliberately: Mindless repetition has limited returns. Deliberate practice—focusing on the hardest components, seeking feedback, and pushing just beyond one’s comfort zone—is what drives structural plasticity and expertise.

Conclusion: The Lifelong Learning Organ

The most profound revelation of modern neuroscience is that the brain is not a static, hardwired machine. It is a living, adapting, self-rewiring organ—a learning machine by its very design. Every thought, experience, and practice session leaves a physical trace, sculpting its landscape. This empowers us with a radical idea: we are not fixed by our genetics or early experiences. Through deliberate, informed effort, we can guide our own neuroplasticity. We can strengthen the neural pathways of resilience, curiosity, and skill. In essence, to learn is not just to acquire information; it is to participate consciously in the ongoing construction of our own minds.